November 2018

As our minds start focusing in on Christmas after a warm summer and mild autumn, the elephant in the room not receiving much attention at the moment, is the continued dry weather which could drive us into a 3rd dry winter. Whilst we are all enjoying a November that doesn’t involve the typical 3 inches of mud to contend with, what does this mean for the environment?

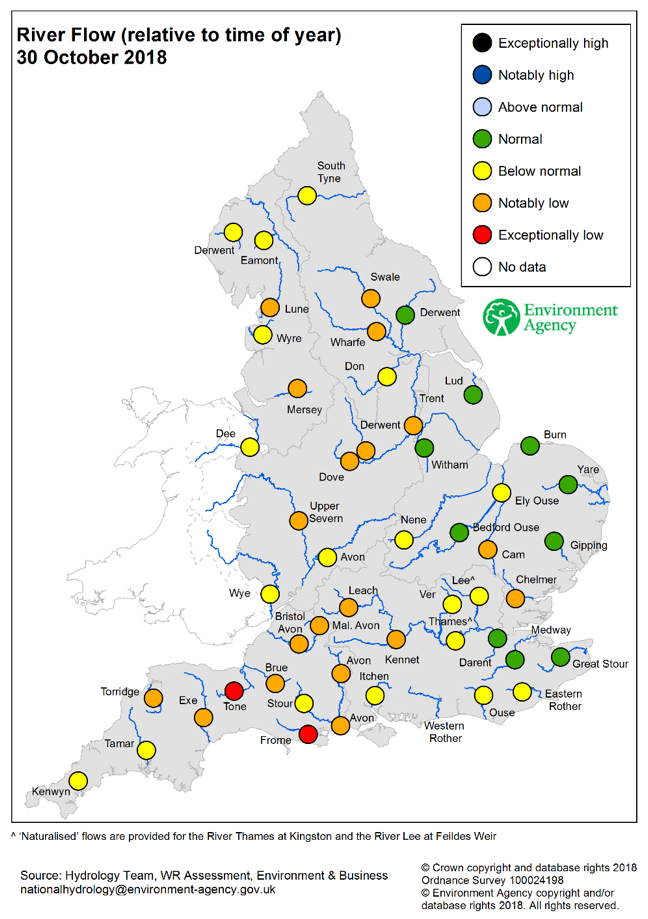

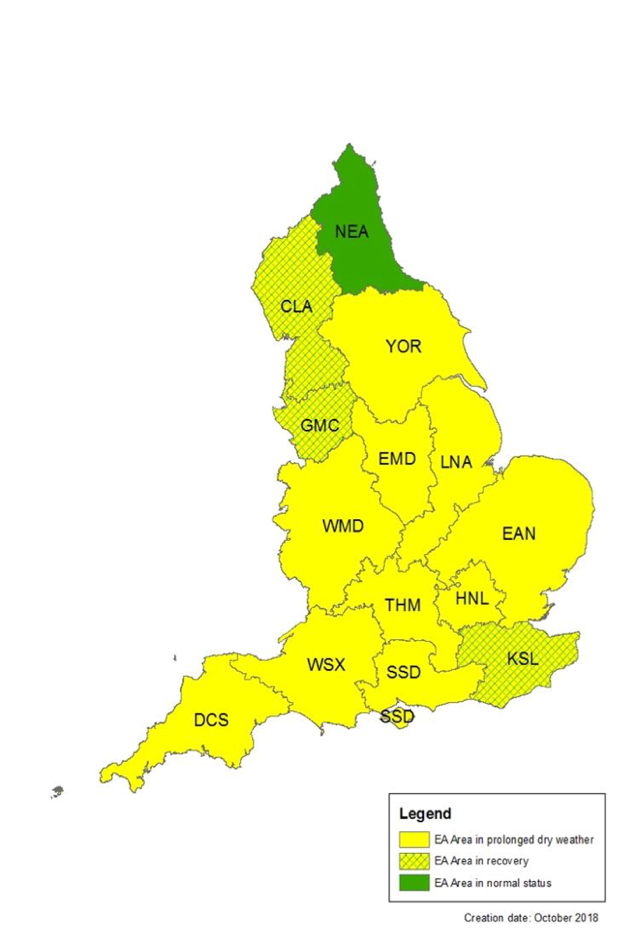

Environment Agency (EA) data shows river flows, as of 30 October, are below normal or notably low for most of the south and west of England and all but 4 EA areas are classified as in prolonged dry weather. Reservoirs in the Pennines and south west are still at risk from lower than normal levels going into winter. And the continuing dry autumn and consequent high soil moisture deficits, look set to result in a continued delay of winter groundwater recharge in southern and eastern counties.

Figure 1a) river flow (relative to time of year) 30 October 2018

1b) EA areas in relation to dry weather

For fish and our chalk streams the impacts of low flow will start being felt now. Reduced groundwater will severely impact the resilience of our chalk streams, and the low flows will increase siltation and die off of water crowfoot, which is a crucial part of the ecosystem.

Reports around the country suggest this year is looking catastrophic for salmon. Salmon spawning should be occurring between now and end of January, but low flows in the summer and up to now, have meant salmon arriving in our estuaries are delayed or just never entering freshwater. They need sufficient flow to encourage them to run, and many in-river obstacles (even fish passes) only allow access above certain water heights.

If the fish do manage to make it upstream, past all the predators (from which they have less cover to hide), the loss of wetted area will severely impact the whole year classes of juveniles, forcing them to lay eggs in sub-optimal locations.

If the low flows continue to May 2019, this will also impact downstream salmon and sea trouts molt migration, as well as coarse fish and lamprey spawning for the same reasons.

These are of course not the only impacts of low flows; others include:

Low flows and, indeed, droughts are natural events and healthy habitats and species populations tend to be resilient to them. However, with only 14% of our rivers currently classified as healthy and salmon populations in a dire state, the potential impact of these weather events this winter is very worrying. We can do little about changing weather patterns, except to address man-made impacts, but we can collectively lobby government to take excessive water abstraction – and its solutions – more seriously, especially the need for water companies to find new sources of water that have less impact on the environment.

That means solutions which will include increasing demand management, improved natural and man-made water retention in catchments and, where necessary, reservoirs or desalination plants. Above all, we have to make sure that government departments, Ofwat etc fully appreciate that ground waters and many of our rivers just cannot take existing levels of abstraction, let alone the increases expected in areas of massive new housing and infrastructure construction. We must continue to press ever harder for government commitment to protecting the water environment, and a new, enlightened approach to abstraction policy seems a great place to start.

Janina Gray is Head of Science & Environmental Policy at Salmon & Trout Conservation.

Follow @drjaninagray and @SalmonTroutCons

The opinions expressed in this blog are the author's and not necessarily those of the wider Link membership.

Latest Blog Posts