July 2021

Last month Wildlife & Countryside Link launched its State of Nature Data survey. This article serves to put the survey in context and explain its potential importance.

In 1995, the former Department of the Environment published Biological Recording in the United Kingdom - Present Practice and Future Development as a report plus appendices. The report was produced by the Co-ordinating Commission for Biological Recording, established in the wake of the Linnean Society’s 1988 Biological Survey - Need and Network report. The two reports were immensely important and provide a still valuable introduction to the complexities of biological recording in the UK, which grew out of the immense public interest in natural history and proliferation of local societies during the Nineteenth Century. [i]

A quarter century ago, there were no instant Internet surveys and the CCBR report incorporated an analysis of 355 responses to a 69-page questionnaire posted to 600 recipients. Together with follow up phone calls and visits (no Zoom!) this was a huge undertaking that ran from 1991-94. The report’s publication led to the establishment of the National Biodiversity Network Trust in 2000 and the NBN Atlas now provides access to more than 200 million biological records, with Local Environmental Records Centres providing information services locally, and many National Schemes and Societies sharing data directly or via the Atlas.

However,

Whilst the sequence of State of Nature partnership reports up to 2019 have done a marvellous job of harnessing available information to highlight the extent of the impact of major pressures on wildlife in the UK and individual countries, both since the 1970s and in recent years, employing recent statistical approaches to achieve this, they have also flagged up data deficiencies, even at a country level, e.g. with regard to understanding and responding to trends.

Since the CCBR report there has been no thorough evaluation of biological recording nor wider environmental information provision for either England of the UK as a whole. In contrast, the Scottish Biodiversity Information Forum’s review made key proposals for the Scotland’s terrestrial biodiversity information infrastructure, highlighting significant return on investment. Unfortunately, these still await backing in any form from the Scottish Parliament. However, the SBIF Review did inform aspects of the recent eftec-led Cabinet Office report on species data flow in England and it will be interesting to see what that leads onto and how the pilot for the Natural Capital and Ecosystem Assessment announced by George Eustice last year might contribute.

Environmental information provision and use, and the supporting recording and information management infrastructure which these require are all too frequent blind spots across Government, local authorities, and NGOS. Outside of the corporate requirements of individual organisations (e.g. Natural England, JNCC) there has never been an evaluation of what information we need about the natural environment for different purposes and at different geographical scales (as proposed by the National Forum for Biological Recording in 2011) and the extent to which required data are collected and used. This would seem fundamental to effective strategy and policy formulation, to targeting funding, efficient monitoring, informed decision making and the aspirations of Government and Environmental NGOs alike, yet the Government’s 25 Year Plan to Improve the Environment has no underpinning evidence strategy.

The Environmental Audit Committee’s damning Biodiversity in the UK: Bloom or Bust report highlights a number of the key issues and makes some associated high-level recommendations. What results from these will be critical and if we consider the various initiatives to be brought forward in the Environment Bill (now at Committee Stage in the House of Lords), e.g.:

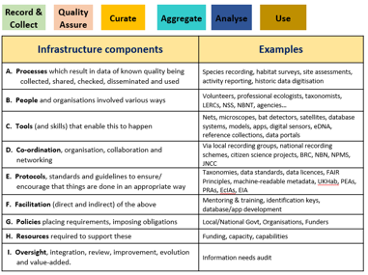

it should be apparent that these demand the use of a range of environmental data, including from Earth Observation, eDNA and other information sources that didn’t exist when the CCBR survey was in progress. But we also need the means to harness these data and to guide, monitor, assess and report on actions and outcomes from site to national level. However, if we look at what needs to be in place (Figure 2), to ensure that needed data are collected in appropriate ways, shared in standard formats with supporting meta-data, so that they can easily be found, accessed, and used and re-used for many different purposes – ant to integrate all of this effectively, it is quickly apparent that a coherent information infrastructure for England and the rest of the UK is decidedly lacking.

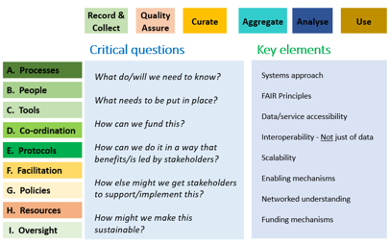

In a hypothetically-ideal world, a well-integrated, well-resourced infrastructure would already be in place and able to accommodate the needs of the 25 YEP, associated environmental legislation and potential changes to the planning system. Understanding the very different information needs of different sectors, how they relate to each other, and how we can ensure that data from different sources may not only be made readily accessible in full accordance with the FAIR Principles but can and will be put to use seems fundamental to achieving the aspirations of the 25 Year Environment Plan and to setting and monitoring progress against definite targets. We are still far from that point, however, and seemingly reliant upon the possibility that secondary legislation might identify, implement and sustain what is needed.

As highlighted by the EAC, there is a clear and urgent need to do things differently and if we don’t – at last – get environmental information provision and its support right, we will continue to be planning to fail. That’s something we no longer have the time nor the resources to recover from – and it isn’t acceptable.

A vital first step toward this bold, new world, will be an audit of existing and future information needs and of the information systems and overall information infrastructure structure that needs to be in place. Towards that, and dealing with where we are at right now, brings us back to the current Link survey. The survey isn’t targeted just at ‘data practitioners’ but also at those who need environmental information in support of their very different goals, including for natural capital accounting; planning; development; nature conservation; rewilding; education; research; setting or meeting policy requirements or deciding how to allocate environmental funding to best effect.

If you fall into one of these or related categories or are involved with steps in the data pathway or infrastructure components then Link needs you to contribute your views in response to the relevant sections of our questionnaire and to encourage those you work with to do so too. The survey is presently due to close on July 9th but we will take account of responses received after that time.

[i] D.E. Allen (1976) The Naturalist In Britain – A Natural History. Allen Lane, London.

Steve Whitbread is a Director at the Association of Local Environmental Record Centres (ALERC) and Biodiversity Officer at London Borough of Harrow.

Follow @_ALERC_ on Twitter.

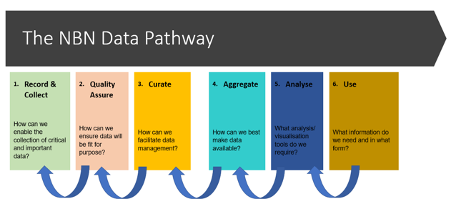

Figure 1: Meeting Information Needs. Whilst the collection, processing and aggregation of data for eventual uses flows from left to tight along the NBN data pathway, we need also consider such pathways from right to left if we are to ensure that information needs can be met, resources allocated and data collection targeted and supported appropriately.

Figure 2: Information Infrastructure Components. Meeting information needs is dependent on having the right components in place to facilitate the steps along the data pathway from effective data collection through to the right information being available for a particular purpose or many different needs. These components fall under 9 headings which all require consideration.

Figure 3: Basis for Environmental Information Infrastructure Audit. If we are to put in place the means to meet local, national or corporate information needs about the natural world in order to minimise harm, deliver nature’s recovery, support sustainable development and ensure the wise stewardship of our natural capital, the key elements to provide the required infrastructure components and facilitate data flow all need to be in place and these critical questions need to be addressed. This also provides a basis for assessing and improving the fitness of what presently exists.

The opinions expressed in this blog are the author's and not necessarily those of the wider Link membership.

Latest Blog Posts

July 2021

Latest Blog Posts